The Narrowband Republic

Unfortunately the chancellor is correct: For many germans the internet is still new territory in 2013. The Merkel government is sleeping through the conversion to broadband, one of the most important economic challenges of our times. This report shows how weak the german net is: For many germans the internet is still new territory in 2013. The merkel government is sleeping through the conversion to broadband, one of the most important economic challenges of our times. This report shows how weak the german web is and what’s working better elsewhere.

with Ole Reißmann for Spiegel Online, June 2013

The USA, Japan and Switzerland – in many countries the internet is faster than it is here in Germany. Millions of households in Germany have absolutely no access to a service that’s fast enough for the data-intensive internet applications of today.

For years, the Chancellor promises fast internet, over and over again. Around 2009 Angela Merkel assured us: By 2014, 75 percent of German households should be able to access data from the network at a rate of at least 50 Megabytes per second.

This promise was not to be kept.

The Providers are shying away from investment and the state largely stays out of it. The result: according to service provider Akamai, on average users are surfing the net with just six Megabits per second. The result: According to service provider Akamai, users are surfing the net on average with just six Megabits per second. But that is not even enough for a TV stream in High Definition. For that about 60 megabytes of data would have to be transferred per minute.

When we use an international comparison, Germany lies at best in the midfield range. 90 percent of users have fewer than ten Mbps. So over 40 Mbps less than Merkel had promised.

But is that at all a problem? And if so, why is that? And what can we do about it? We answer the most important questions relating to broadband internet.

1. Do we really need fast internet access anyway?

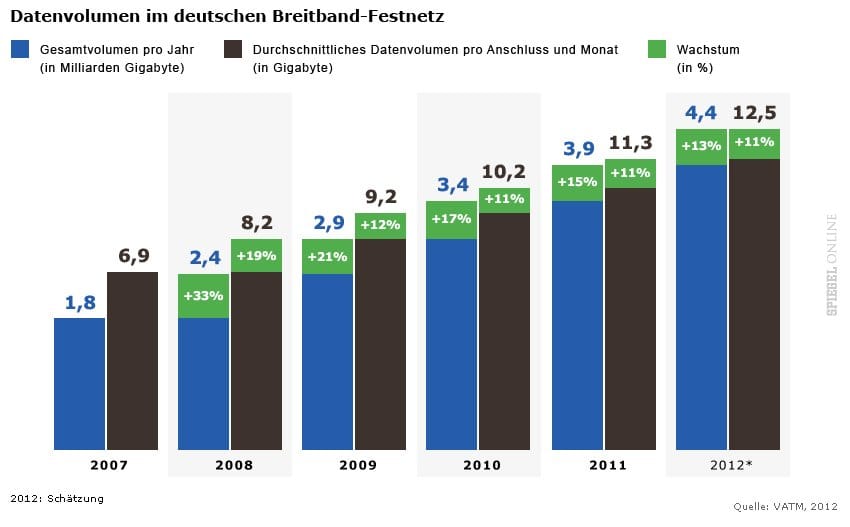

Yes, at least in the medium term. The volumes of data are rising rapidly: more devices, more video streams and television over the internet. Each year and for many years now, the customers of German providers are accessing more data from the net:

This growth will accelerate significantly. Online video stores are booming, television stations are expanding their digital offers. Flat rates for streaming, such as Watchever, are coming onto the German market with competitive prices and new game consoles should make internet TV even easier – and perhaps Apple TV is coming soon anyway. With video streaming on the net, “We are still at the very beginning of development”, says Stuart Cleary from Akamai – who of course has an interest in the growth of his industry.

But also in the independent infrastructure – expert Richard Sietmann from the trade magazine “c’t” predicts enormous demand for broadband.

“Sooner or later, everything – from TV programs to the children’s birthday party – will be streamed in and out of households. Other distribution channels such as DVB-T or satellite TV will soon be a thing of the past. This is an enormous social and industrial policy challenge, comparable to electric mobility or the energy revolution.”

More bandwidth also attracts more usage with it. The lower the bandwidth, the less content the user can access from the net. The average volume transmitted by type of connection in Germany illustrates this. Narrowband internet users access on average a quarter of the data volume of broadband surfers.

2. According to the Merkel government there is sufficient broadband. Is that correct?

This is window dressing. There is no uniform definition of what broadband internet is. Instead of letting things run their course within the limits of the past, one should orientate towards a future-proof broadband strategy according to demands of the medium term.

This is how the internet enters the home:

- DSL: The advantage of this technique is that a cable leads to every customer. However, the bandwidth is limited. In addition, the transmission bandwidth decreases with the length of the cable. The advantage of the technology: The cables are already in the ground and they are amortized. The providers do not need to invest a lot.

- The cable television network: With television cable, multiple customers share the available bandwidth, sometimes even hundreds of households.

- LTE cellular radio technology: With the radio cellular technology standard LTE, the bandwidth for every user drops, the more users there are accessing data in a radio cell. The advantage of the technology: It’s relatively cheap – a radio tower can cover the whole neighbourhood.

- Fibre: The only truly future-proof technology for broadband internet. The range does not decrease with distance. There is barely any limitation on the transfer rate. Once the fibre is installed, broadband upgrades are possible without re-digging. However, the laying fibre optics costs more than the upgrade of existing copper lines and cable television networks.

For good quality internet TV, you need a connection of eight Megabits per second. About half of the 30 million German households with internet access currently have a slower connection. The engineer Martin Fornefeld whose consulting firm Micus also works for government agencies, evaluates the opportunities in Germany for HD television on the net in this way. “Statistically speaking, half of households have never had this service. By the way: If you have two TVs at home, you already need 16 Mbps. ”

Half of all DSL customers have a subscription of less than six Mbps; one fifth of German DSL users are surfing with narrowband of less than two Mbps.

This is not least an economic factor: As a result, especially in underdeveloped regions such as Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, these companies are not setting up yet because they are not able to anticipate sufficient internet uptake. The more digitized the business world becomes, the more urgent the problem will be.

3. By world standards, germany is in good shape, right?

No. In terms of actual measured broadband width, our standing could even be called poor. The average speed for all internet connections in Germany of six Megabits per second, is only even mediocre when compared to rural USA.

4. Will everything be alright with super fast v-dsl?

Perhaps in the short term it will be better. But in the medium term V-DSL is no solution. There is a technical problem: bandwidth with DSL is limited by the copper cable.

V-DSL gets something more out of the old technology. Part of the connection runs via optical fiber, but the last mile to the house is still copper:

DSL is slower than other transfer technologies and in addition the bandwidth decreases with cable length – a problem in the countryside, where there are often large distances between cable distributors and households. With fibreglass on the other hand, distance does not put a brake on this.

In the medium and long term, fibreglass is the superior technology. Richard Sietmann from trade magazine “c’t”: “All DSL technologies – from ADSL to VDSL2, to vectoring – come up against the physical limits of copper wire pairs.”

The second problem with V-DSL: This technology not only makes use of an outdated infrastructure, but also benefits the former monopoly holder Deutsche Telekom. Most Internet users surf using DSL – and this market is firmly in the hands of Telekom:

84 percent of all broadband connections in Germany run through the old copper lines, more than half over Deutsche Telekom. V-DSL is expected to strengthen the market position of Telekom. Because the Group is allowed to use such connections exclusively, the new technology does not need to rent out from the competition as was the case with the previous DSL infrastructure. The Federal Network Agency has approved this exemption. To put it bluntly: Telekom may monopolize a part of its copper network again.

84 percent of all broadband connections in Germany run through the old copper lines, more than half over Deutsche Telekom. V-DSL is expected to strengthen the market position of Telekom. Because the Group is allowed to use such connections exclusively, the new technology does not need to rent out from the competition as was the case with the previous DSL infrastructure. The Federal Network Agency has approved this exemption. To put it bluntly: Telekom may monopolize a part of its copper network again.

5. Why is the expansion of fibreglass in germany so poor?

The large providers are investing little in the technology At the start of 2010, Deutsche Telekom CEO René Obermann announced the arrival of the “Gigabit society” and promised: To the end of 2012, Telekom is connecting up to four million households to the net via fibreglass. Little has come of it. 360,000 households are able to get a fibre optic connection with Telekom. Fibreglass is in short supply in Germany. The number of reachable households rose by just 290,000 from 2009 to 2012.

Spending by providers on network extension has been consistently below the highs of 2002, 2007, 2008. The interest rates are currently low, and the demand for bandwidth increases:

Deutsche Telekom invests less than its competitors and is counting on the expansion of their DSL infrastructure.

Thomas Plückebaum from the Scientific Institute for Infrastructure and Communication Services (WIK) accounts for it thus: “Telekom’s good copper infrastructure is Germany’s curse and its blessing. VDSL is the last gasp of this technology, the more it is exploited, the later fibreglass will come.”

6. How much would fibre for the whole of Germany cost?

Blanket coverage, fibre-optic expansion into German homes is likely to cost billions. The Scientific Institute for Infrastructure and Communication Services (WIK) estimates that 70 to 80 billion Euros would be needed.

Investments pay off sooner when more people live in an area and the more major distributors are there. This relationship is a visualization of the broadband investment index: In the big cities, it looks good, everywhere else, bad to abysmal.

The result of the regulation of telecommunications in Germany so far: In the cities there are more suppliers, and bandwidth is increasing. In the countryside there is little broadband competition and hardly any expansion. Thomas Plückebaum from the Scientific Institute for Infrastructure and Communication Services (WIK) analyzes it as follows: “Deutsche Telekom has expanded VDSL in large cities. Competition exists in Cologne, Hamburg and Munich because competitors can only overtake Telekom VDSL with fibreglass. In the countryside it is very different because people are happy if anyone offers any kind of alternative at all. ”

7. Fibre expansion is surely poor in other countries too?

No. In many countries, the network is better developed. In many countries the fibreglass ratio is significantly higher than in Germany and is highest in Scandinavia and some Eastern European countries.

.

In Sweden, Latvia, Bulgaria and Norway, fibreglass ratios are high – and that’s despite some poor conditions.

The broadband investment index for Europe outlines better conditions for Germany for the deployment of broadband networks than these countries. The index is calculated as a product of population and distribution frames per square kilometre for urban and rural districts.

The more residents and the more major distributors there are in a region, the more favourable and more lucrative upgrading is (more customers, more existing infrastructure).

8. What can be done now?

Some Ideas for broadband expansion:

- New technology: The most expensive part of fibre-optic expansion is the digging of roads. There are much cheaper methods. With micro-trenching for example, the asphalt is milled in one procedure and the fibre optic cable is laid 20 to 30 centimetres deep. Construction companies lobby against such cheap methods, there is also resistance within communities.

- Coordinated installation: in countries such as the Scandinavian states, Slovenia, Israel and the United States, fiber optic cable is laid down when other construction work takes place. If the street is being torn up for new water, gas or local geothermal heating pipes, you might as well also lay down fibre optic cable.

- Money for the countryside: The broadband market in Germany is divided. In cities there is competition, in the countryside, at best, only ever one true broadband product. This is the consequence of regulation: It is not possible that prices fall and the vendors put a lot of money in the broadband expansion in the countryside at the same time, where the challenges are greater than in the city. To put it crudely: In cities there is competition and cheap broadband, because the providers are making savings particularly in rural areas. Telekom also does that in the city, but with VDSL2 instead of fibreglass.

- A universal service: A solution to the urban-rural divide: Lawmakers could oblige providers to provide a minimum bandwidth to all customers, just as Post also has to deliver anywhere throughout Germany. Nico Grove, Professor of Economics at the infrastructure Bauhaus University Weimar advocates true broadband as a universal service: “This is a highly effective and efficient approach to achieve the coverage. The cost of the expansion would be imposed on the operators, they would then therefore consider these expenses for the purposes of network planning and pricing. “The FDP, CDU and CSU rejected a law in late 2011 for a universal broadband service.

- Public utilities: In Sweden, the fibre-optic network will be expanded mainly by municipalities and regional providers. Thomas Plückebaum (WIK): “In the long term refinanced expansion does not fit in the shareholder philosophy; Telekom is subject to these constraints of the stock market as much as Vodafone or others.” However, many municipalities have sold their telecom providers and fibre optic networks to corporations. Given the high debt and numerous areas of compulsory expenditure (daycare, Hartz IV policies), municipalities have other priorities. Moreover should local authorities cross-finance broadband in metropolitan areas through subsidies?

- Federal government: So far, the federal government pushes responsibility for the deployment of broadband networks over to municipalities. They need to deal with financing, access, funding, and cooperation. The unequal supply in Germany is reasoned away.

Conclusion: Expansion so far has been insufficient. The technology of the future, fibreglass, is a niche market in Germany. Deutsche Telekom is able to market its copper piping in an unregulated way as VDSL2; for large suppliers there little economic incentive to invest in unprofitable areas. The crucial question voiced by the government thus far: Is broadband internet a public good and is it in the public interest? If so, the federal government needs to do more.

Sources

- Akamai: State of the Internet 4/2012

- Breko: Marktdaten 2012

- Ronald Freund: Glasfaser auf dem Weg zum führenden Medium

- Dialog Consult / VATM: 14.TK-Marktanalyse Deutschland 2012

- Bundesnetzagentur: Jahresbericht 2012

- ICT Fact and Figures 2013

- BIIX e.V.: Breitband-Investitionsindex

- Auskünfte von Thomas Plückebaum (WIK Conult), Martin Fornefeld (MICUS Management Consulting), Richard Sietmann (c’t), Akamai, BIIX e.V., BUGLAS, FTTH Council Europe, VATM, Deutsche Telekom, Stuart Cleary (Akamai)

Converting from Mbits into Megabytes

The data throughput for broadband connections is specified in megabits per second.

This is confusing because disk space is measured in Mega- and Gigabytes. The conversion is actually simple: Eight bits equal one byte. The conversion is complicated by the fact that information on disk space is given in a mix of binary and decimal (detailed explanation here). The table below will help with these concepts, Heise offering a good bandwidth calculator for free, with which MBits per second can easily be converted into Gibi- and Gigabytes per minute or per second.