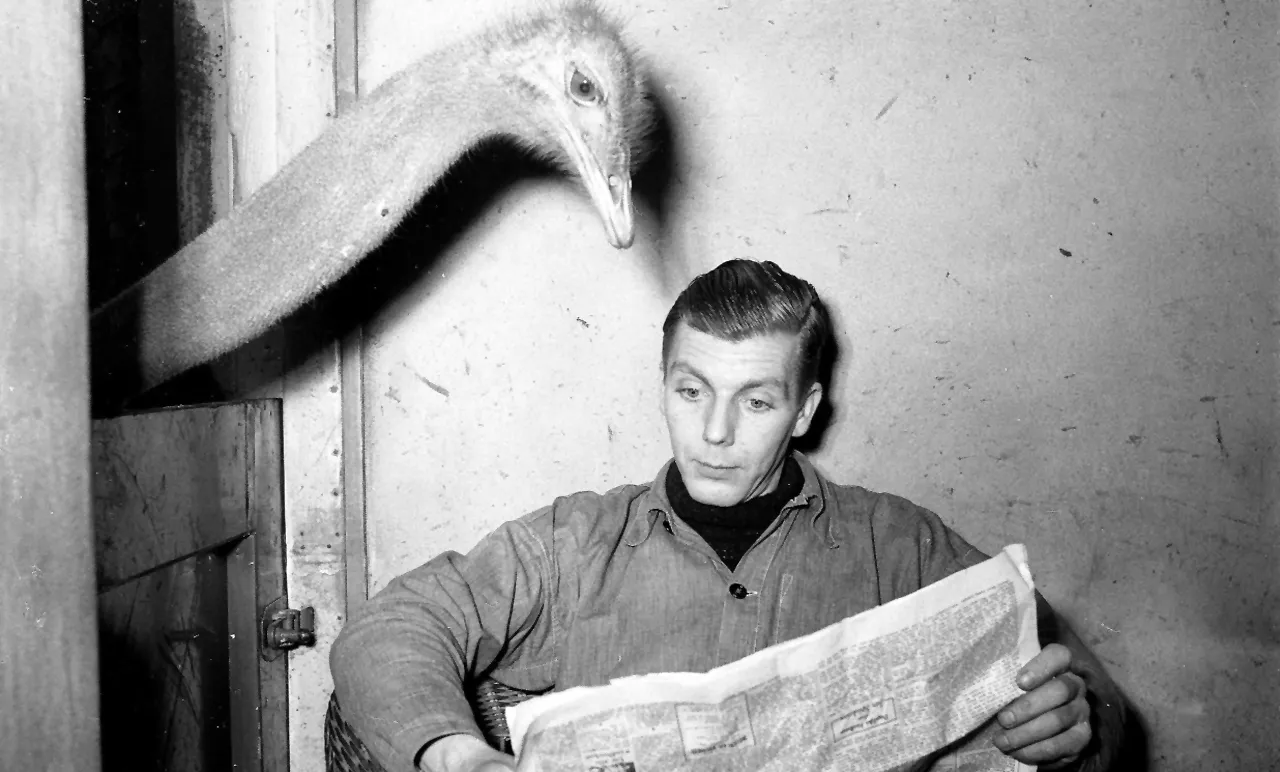

After work

So much for Krupp’s company town: Since 150 years Essen is constantly reinventing itself: agricultural landscape, service center, European Capital of Culture. One thing remained the same: The city grew with the dreams of it’s immigrants.

Essen’s image could only get better. In 1924 the great reporter Egon Erwin Kisch characterized the Ruhr metropolis very vilely, without writing a word about the city he said everything: “With the express train it’s hardly an hour to beautiful, bright Dusseldorf, where Heinrich Heine wrote, Richard Wagner composed and Achenbach painted.” Today no one rants about Essen like this. On the contrary, today Esseners abroad no longer speak of their home ashamed as somewhere “near Cologne”. Instead, they list superlatives. Essen? That’s the European Capital of Culture 2010. There you can watch movies in Germany’s largest cinema – since 1928. There a coal-mine with the main buildings built in Bauhaus inspired style is part of the UNESCO World Heritage. There trade associations founded in 1993 Germany’s largest private university. There nine of the hundred largest German companies have their headquarters. But who hears all this, thinks how Kisch did: Essen may hold some record, but it has no flair, no soul. “Factory suburb,” Kisch called Essen. That has never been true, but bias sticks. For superlative tell nothing about the soul of Essen. Anyone who wants to discover it has to take the tram.

A great poet has done that in Essen in 1926. Joseph Roth came to Essen, took the tram and was amazed: “The city does not stop. But even if it end immediately another one begins. ” Essen has exploded, from 5,000 inhabitants in 1820 to more than half a million of 1926, when Roth visited the city. Anyone who wants to discover Essen on Roths trail, takes the tram 107. On the 17 kilometers from Essen’s rich Southern district of Bredeney through the centre and the poorer northern districts to Gelsenkirchen central station passengers experience in 46 minutes a greater diversity than in a whole afternoon in Berlin-Mitte. The train runs through residential areas, service centers, industrial sites, cultural centers, housing estates, trendy neighborhoods – everything is one city, everything is Essen.

The 107 starts in the south of Essen, the Ruhr heights in the elegant district of Bredeney. Here Alfred Krupp enjoyed the view of the lake Baldeney. In 1873 he moved into his Villa Hügel – a palace with a marvelous view over the woods and hills of the south, that was very modestly called a detached house in Essen’s cadastral register. In fact the 269 rooms and 28 acres of parkland around it are a powerful symbol of industrialization in Germany. Three generations of Krupps lived there, today the tram 107 brings tourists in the vicinity of the property. Somewhere in Bredeney (incorporated into Essen in 1915) Germany’s two richest entrepreneurs of the present are at home: Karl Albrecht, owner of Aldi Nord and his brother Theo Albrecht, owner of Aldi Süd.

At the tram stop Bredeney there is nothing to notice about super-rich neighbors. Certainly, you won’t find seven boutiques with women’s clothing along a block at the main street, in every neighborhood. But more striking is the green landscape. On the weekend you see wanderers with backpacks marching from the nearby forest to the tram. They come up from the Ruhr valley. Down there is the lake Baldeney, where each year a large Regatta, the Essen week takes place.

South of lake Baldeney, the gentle slopes, fields and groves look like Essen did 150 years ago. Back then the city overran an agricultural landscape unchanged since the Middle Ages. Villages suddenly became neighborhoods, the neighborhoods became new homes for hundreds of thousands of immigrants form East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia. The immigrants’ dreams spurred the growth of Essen. The dreams of a better life were great, the city flourished rapidly. Essen never had the time to create something whole and new from the old villages, the new districts populated by immigrants and the industrial areas. The town just grew over everything, and became a new place every year. Something like this is supposed to have happened in Berlin five years ago, when people flocked to the urban wasteland where they found “a tender poetry, abandonment” as one of the newcomers, Georg Diez, described it. In Essen this feeling exists since 150 years. Anyone traveling with the 107 through town, feels it.

From Bredeney the tram rolls downhill towards the north, toward a different Essen. At the foot of the Bredeney hill some turn-of-the century villas glide by, at the border to Rüttenscheid some advertising agencies follow, an IT company that works for the Swiss Post and then the tram moves underground, runs below Rüttenscheid, a district one should see above, too. The passengers who board the tram at Rüttenscheider star look different than in Bredeney. Most of them are younger than the passengers in Bredeney and many are well dressed: Young women often carry handbags, rarely sneakers, men wear slim-cut suits that fit them very well. This is Rüttenscheid. Here, people sit outside, drink coffee in the sunshine and sometimes you see soccer legend Otto Rehagel doing that at the Café Mondrian. But that’s not all there is to Rüttenscheid. Not everything is chic about that district. In a side street resides on a backyard Magmafilm, a leading porn studios in Germany. Founded in the early 90s by Walter Molitor, transformed into a global player by his son Nils Molitor. And at the end of the very same road you find one of the leading auditing and consulting firms in Germany. And opposite, in an old crippy, one of the best and a few vegetarian, even vegan restaurants in the Ruhr: the Zodiac. Mohammad Golestan Parast has opened it in 1987. He had fled from Iran, learned German in Essen and fulfilled the dream of his own restaurant. He came with the same hope for a better life to Essen like so many before him did: First the peasants from East Prussia and Silesia, then in 1950 the Italians and Greeks, and later Turks. They built the city and reinvented it. After the Second World War, 60 percent of the city area were destroyed. The industry flourished for a last time, but already in the sixties the shift to a service economy began. Coal mines and huts were closed down, new white-collar jobs created in trade. Today, three quarters of the jobholder in Essenes are employed in the services sector.

A tram stop north of Rüttenscheider Stern this new Essen looks best: around the 69,000 square meters of the city park you find the Philharmonic Hall, the Aalto-Theatre, the square towers of glass and the round beacon of RAG, RWE, headquarters of Hochtief and Steag. In the summer young people lie in the grass between these buildings, and under the shady trees in the avenue at the edge of the park older men play boule.

From this idyll it’s just a few meters to the central railway station, until 2008 the ugliest in Germany, now a kind of shopping mall you have to squeeze through to catch a train. Here a young woman with rather big, black glasses boards the tram 107. She will get off at the Zollverein World Cultural Heritage site. Of course. Elsewhere in the north, in the district Katernberg for example you rarely people with these kind of glasses. The boys here wear baseball caps, some have rather pale denim jackets with RWE-badges (RWE as the soccer legend Rot-Weiss Essen, not like the corporate group, which happens to be called the same), the old men were to narrow or too wide plastic jackets. So what? Jackets do not make people lovable. But the worry about coldnes does, that the Italian father in his thick padded jacket struggles with until he allows his two boys to take the striped woolen caps off. The bashful smile of the old Turkish men with a herringbone jacket and walking stick, who tries to pick the right ring tone for his cell phone. It just hums, he looks up, raises his shoulders and smiles, embarrassed.

North of downtown Essen the 107 leaves the tunnel again. On the right the Jaguar dealer offers a couple of Cadillacs, on the left are allotments. Carved wooden signs name the proud owners. at the Herbertshof old men in too-tight jackets stand beside a transformer box. On the box they have parked their beer bottles to gesticulate better in the conversation.

Truly in the north you feel when the tram is rolling down the Kapitelberg in Stoppenberg. The tram rolls down the hill north-bound and there you see the World Heritage Site Zollverein. Are the cooling towers, the gas flare, the chimneys still blowing something into the air? No, the clouds hang low. And then suddenly there is some blue sky. Industrial Heritage idyll.

Zollverein is for Katernberg more than a beautiful backdrop. 220 jobs were created here already, on the former colliery site at the Founders Center “Triple Z” small firms flourish. Katernberg and its 24000 inhabitants are still in the midst of the reinvention, the agency and designer area Rüttenscheid went through years ago. 17 years ago, the coking plant Zollverein closed down. Thus, the district lost not only jobs, but its identity. Katernberg had grown with the industry, and now that the industry vanished the district is left behind on it’s own.

The farther the 107 runs to the north, the more solariums, phone shops and sports betting shops catch one’s eyes. How many nations make up the Katernberger mix, no one knows for sure. At Katernberg Market the travel agency is named Parsczenski, the refreshment stand at the tram station Abzweig Katernberg is called Karaüzüm, but offers the standard repertoire of high-area kiosks: sandwiches, spirits, tobacco.

On the track to Gelsenkirchen the 107 passes some miners’ housing estates: Glückauf, Meerbruck, Ottekampshof. In some gardens here you still find a dovecote. And Sunday at noon, the old pigeon fanciers are sitting at the “Zollverein Klause”, drink beer and see whose pigeons won the race.

On Thursdays you can find the old miners a few tram stops further north with the 107 at harness racing track in Gelesenkirchener, which almost stands in Essen – you don’t notice leaving one town and entering another in the Ruhr area. The sellers of the “trade journal for Harness Racing and horse breeding” (bought by many visitors because of the betting tips) at the entrance has his own theory about the past success and decline of the racetrack: “Every second of the old miners had pigeons. And when the pigeons couldn’t start in bad weather, the miners came to the harness racing. ” And here, with fries and Pilsken (pet name for pilsener), overlooking the race and the refuse dumps in the background you feel something you find only in the Ruhr area. The city has many souls, a lot of flair and a unique sense of life: it always sets off for something new. Food critic Peter Erik Hillenbach describes it this way in his guide book for the Ruhr area: “A place without its folklore. And yet you felt at home here. Those who left, could never break away from its origin. You took the feeling of brokenness with you, down-to-earth but still deracinated. Even the foreign workers were longing for this feeling after they left. ” Or, as a Portuguese worker who came back to the Ruhr area said: “What am I supposed to do in Portugal?